Ten Little Nigger Girls

Works By Imo Nse Imeh

About The Collection

Ten Little Nigger Girls is a retelling of a children’s book that was written in 1907 by Nora Case, a British author. The children’s book is comprised of racist stereotypes about black people, particularly black children. The story, which unfolds as a nursery rhyme, features a cast of ten black girls, who are each eliminated one-by-one, and sometimes in horrific ways (for example, one of the black girls is burned alive while making toffee, another is eaten by a bear).

As a response to and revision of the original children’s book, artist Imo Imeh’s series of drawings features contemporary black girls in various states of danger, in the present-day. With each drawing, he seeks to examine the language, history, and realities of ongoing racial subjugation in America, the invisibility of young black people, and the misfortune of how we collectively decide the degree to which we ought to place value on the lives of black children.

Forgotten Girl

A little girl appears in two instances—as a girl who has wandered off (unnoticed), and as a lost girl (literally and figuratively). She is immersed in a motif of Forget-Me-Not blossoms. The other main subject in this work, a large inkblot, advances upon her and begins to overtake her face, erasing her identity from existence. This drawing addresses the danger of neglect, and of the apparent invisibility of black children in society—they are largely untouched, disregarded, and left to wander through life’s meandering trails, alone.

In this series, Forgotten Girl is the second drawing that I developed, and the very first one that I stained with India Ink. I played around with different methods of applying the ink, In many ways, it was trial and error. I conceptualized the ink as a dark force attempting to overtake or blot out the girl. Thinking about ink in this way made it easier to “destroy” the original beautiful charcoal rendering of the girl.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

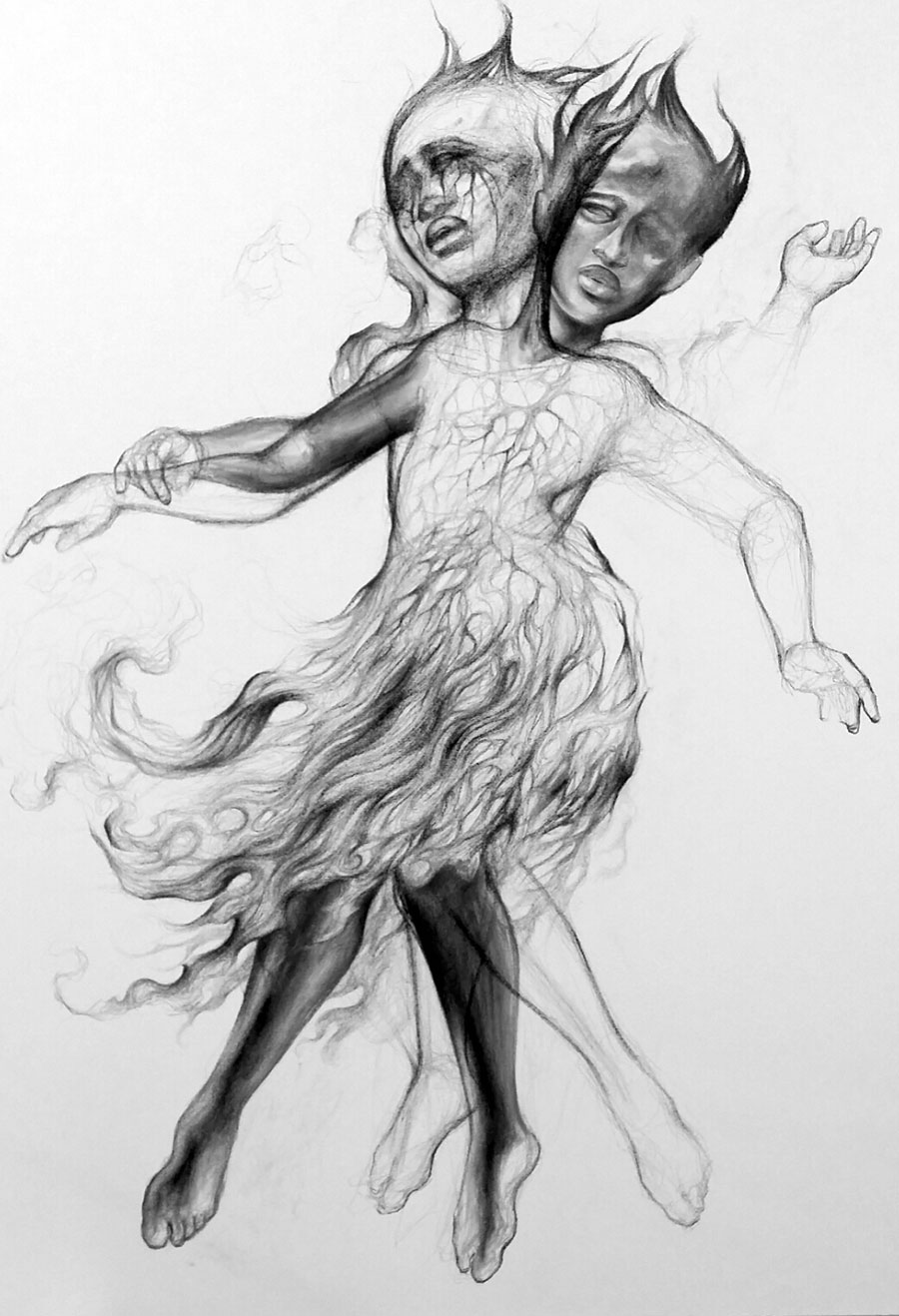

Girl On Fire

This is the very first work that I created for this series. It shows a girl whose dress is composed of the raw energy of a fire, so that, in essence, she is wearing her own death. Of all of the works in the series, this is the single drawing that directly references one of the perils that a little black girl faces in the original nursery rhyme, Ten Little Nigger Girls, in which a black girl is burned alive. This work reveals my own intrigue with the unbelievable notion that in the imagination of anybody, a child being set on fire could elicit amusement in any form, or could be considered appropriate not just for public consumption, but specifically for the attention of little white children to read and reflect upon; a horrific moment, hidden away in the folds of what is disguised as an innocent children’s nursery rhyme.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

Girl Overboard

This work is aligned with other drawings within the series that address society’s impact on little black girls—especially in the form of consumption and manipulation (also view Puppet Girl and Girl on Fire). In this case, I was interested in a few concepts—first, the submersion of the black girl in pure darkness, a sea of thoughts, beliefs, and activities that overtake her identity, to the point of her erasure (or death). I was also interested in the question of how she arrives in this dark ocean. The idea that she was once in a secure place, en route to a desired destination, and then suddenly toppled into a new, dark, and dangerous space (or perhaps was pushed into it) has crossed my mind as this drawing has developed. As with Forgotten Girl and Gone Girl, this drawing also sheds light on the reality of neglect, and the possibility that black girls simply get left behind in dangerous spaces, often to fend for themselves—a set of ideas that would simply never be accepted or tolerated as widespread realities for little American white girls.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

Suicide Girl

This work addresses the issue of suicide—both in the literal sense, and in the more conceptual sense—of black girls. Here, the main subject is a black girl who appears in two instances—first as a figure who has just decapitated a girl, and second as the face of the decapitated girl. The two subjects are one in the same. Here, I recall the the story of Perseus and Medusa from Greek Mythology, in which Perseus, the hero, sets out on an expedition to execute the gorgon named Medusa, a monster who bears a crown of live venomous snakes on her head, and whose appearance turns any onlooker into stone. I was interested in the hero/monster concept, as I contemplated the problem of suicide. In this case, the black girl, who sees herself as the gorgon—the monster—performs the only heroic act she can think of—her own death, by decapitation. In committing suicide, the black girl assumes both the position of heroine and monster.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

Syringe Girl

This work is one of the earlier drawings that I developed for the series. With intersecting figures that are now overcome by large blots of black ink, I wanted to deal with the messiness and realities of drug experimentation among young black girls. In this case, the “trip” or the “high” is something in which we partake as the viewers; we try to focus on the main subject’s face, but are unable to do so with ease—we experience a blurring of forms. Here, the notion of self-destruction, as with some of the other drawings in this series, is highlighted as something in which the larger society is complicit. This drawing addresses the reality that young black girls who stumble into a world of self-destruction are actually victims who need rescuing—a consideration that is often denied black girls who find themselves in self-destructive trouble, especially in the contexts of drug abuse and prostitution.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

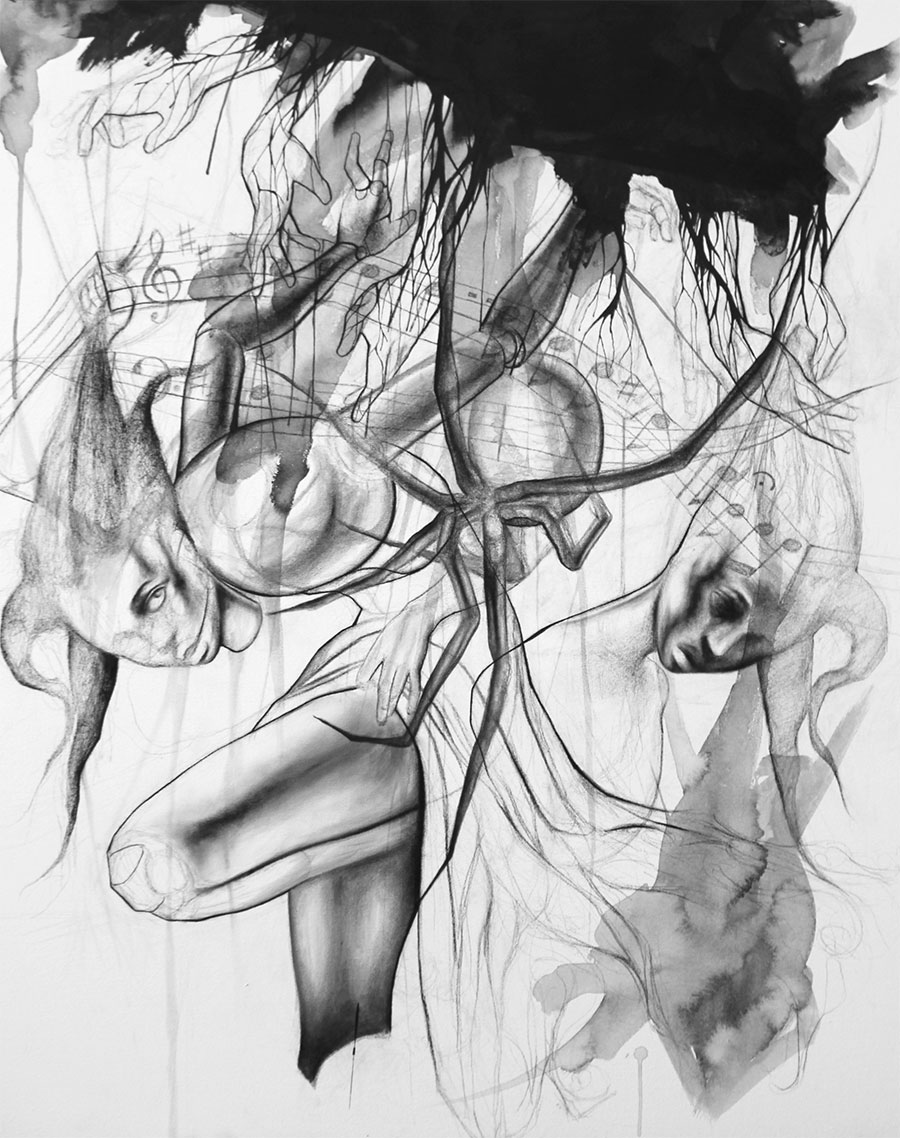

Puppet Girl

A young black girl appears in two instances—in one, she is hunched over, her body and limbs, which bear the articulations of a puppet, are contorted, as outside forces (the hands reaching down from the inkblots above) are in full control of her movements. She carries her own disembodied head with one of her hands, and with another, she hikes her dress dangerously high up her thigh—both of these actions she does only because she is powerless to resist the authority of the puppet masters above; they are “pulling the strings,” as it were, and forcing her to perform her body, even though it is young and already broken (her head is detached, and she is missing a leg). In her second appearance, the image of the young girl is realized in a subject who only has a torso, but who lacks limbs to defend herself or run away. A large Black Widow spider lives in the middle of the drawing, clinging to the threads that bind and control the girl, and speaking to the toxic and deadly nature of her unfortunate situation.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2016

Selfie Girl

Featuring an active cohort of girls in flight, two who pose for selfies, and recoil as black ink erupts from their cellphones to overtake them—this work is inspired by the increasing dangers in social networks in which young girls find themselves. Facebook and Twitter have evolved into public, unregulated spaces of intrigue and potential danger for little girls. I was particularly interested in a series of devastating recent cases in which the reputations of young black girls have been utterly destroyed, either from explicit images/videos that they shared of themselves, without understanding the consequences, or from those taken of the girls without their knowledge, and released into the unforgiving mediasphere for public scrutiny, shaming, and a horrific social death, by way of ostracizing.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2016

Untitled Girl

This work oscillates between compositional beauty and tragedy, in its attempt to capture the horror of sexual abuse. The main subject—a beautiful black girl with her hands attempting to conceal her face—is the embodiment of shame. In this work “shame” follows the act of sexual abuse. The large moths are symbols of the night, when things go quiet, and new dangerous secrets are sometimes formed. The moth is also a creature that is attracted to light—any type of light—sometimes to the point of its own demise. The girl appears in two instances—one as shame, the other as overtaken by darkness. Sexual abuse is not just a black girl problem, obviously. However, my interest in it as a subject comes from the degrees of marginalization to which black girls are subjected. If the powerless and the voiceless are the ones who suffer most from these kinds of abuses, then I am left wondering, constantly, about the untold histories of this particular type of atrocity against black girls (and boys) and the damages that have come as a result.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2016

Gone Girl

A little black girl is carried away by a murder of crows. In this work, crows make an appearance to symbolize peril and death as an intelligent, strategic force that carefully maps out its plan of destruction. I remain perplexed by the high instances of missing black children that are unreported, unsolved, and generally disregarded by an American public that tends to quickly engage cases of missing white children. This disparity in how we as a society collectively decide to show care for white children, without question, versus our cart blanche dismissal of suffering black ones has bothered me ever since I myself was a youth. It speaks to the larger issues of the marginalization and invisibility of black children, both of which are also the impetus behind another drawing in this series titled Forgotten Girl.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2015

Dream Girl

One of the ten girls winds up victorious. A beautiful girl appears in two bold instances, in one hand holding a Jacaranda blossom (native to Zimbabwe), while admiring a dragonfly that rests gracefully on her other hand. The India ink stains, which appear as a representative of darkness and anxiety in many of the other drawings, also overtakes this work. But, the story here is that our main subject, with her enrapturing beauty, persists in spite of the darkness. Dream Girl, as a concept, has been important to this series as a whole, not only because it offers me and the viewing audience some reprieve from an otherwise unsettling series of drawings, but also because it has inspired me to consider a new body of works that will act as counter narratives to Nora Case’s original book. Perhaps what is left for me to create is a series of drawings that challenge the idea of imminent death and despair of our black youth, and instead celebrates their lives. Such a series is very much a possibility.

Charcoal, India Ink, Graphite on Canvas,

48 x 60 Inches, 2016